Everyone has their pick of their favorite Hayao Miyazaki movie. Polling my friend group in what was supposed to be an easy, select one (and only one) film question, resulted in multiple titles being brought up. From an assertion that there was no choosing between Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke, to a refusal to choose between Porco Rosso and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, to a confident declaration that Howls Moving Castle, despite some divisive reactions, is the strongest of Miyazaki’s oeuvre.

Not that it was a quiz or a right-or-wrong type of question, but Princess Mononoke is certainly the correct answer. As it celebrates its 25th anniversary — and as we’ve seen a deluge of animated films in recent months from Netflix, Disney, and Illumination — it’s easy to look back at a nostalgia-lensed fondness for one of Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli’s most definitive films. It’s spectacular and likely the most breathtaking piece of cinema Miyazaki has ever created, a perfect blend of thematic elements, beautiful hand-drawn animation, environmentalist viewpoints, and morally gray antagonists that have become associated with the director.

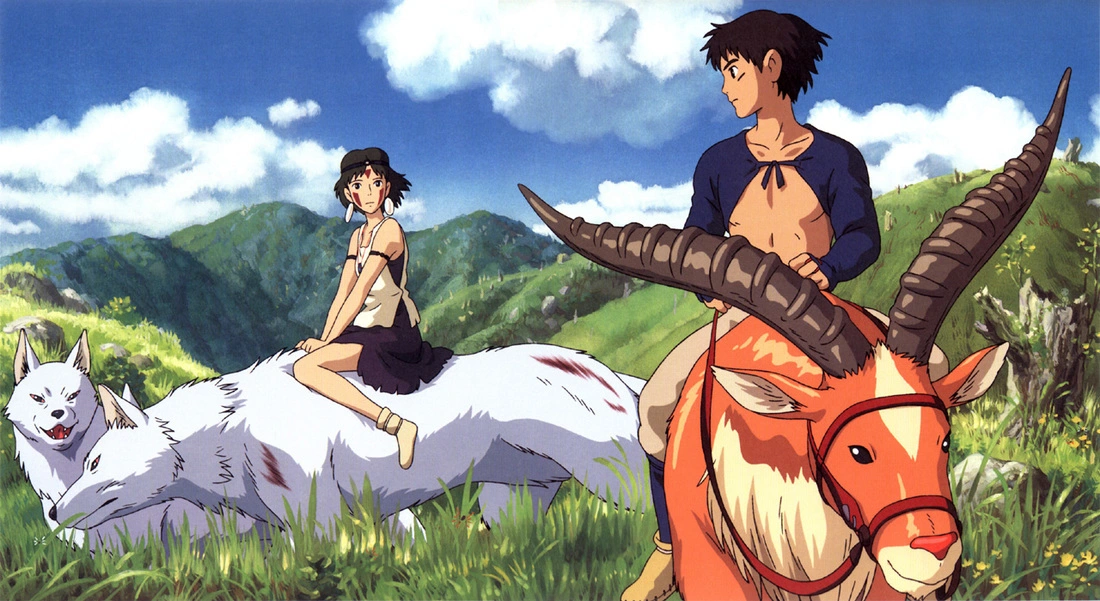

Released in 1997, Princess Mononoke was the director’s seventh feature film and would go on to become the highest-grossing film in Japan that year. Set in the 14th century during the Muromachi period in Japan, the world our protagonist, Ashitaka, is living in has begun to show the strain of humanity not respecting and nurturing nature. After he’s attacked and infected by a rabid animal, he must seek a cure from a deer-like god, Shishigami. While on his travels he encounters the wolf god, Moro, and his human companion, the titular Princess Mononoke.

A more complicated hero’s journey.

Ashitaka, from the start, is far from the perfect hero, despite his most noble attempts to broker peace between the world of the gods and spirits that keep refuge in deep forests and the humans who are so often pillaging the land. He’s naive, something that is set against Mononoke’s (San’s) cynicism and lack of faith in humankind. By establishing the imperfections of his characters early on, it makes it so that every new character we meet, from towering gods to humble villagers, is expected to contain multitudes and, often, elicit compassion from not just the characters onscreen, but us, the viewers.

It would be so easy for Miyazaki, at any point in his career, to rely solely on animation and visuals as the main drawing point. And, frankly, even his lesser outputs are bolstered by some of the finest artistry in the industry. Yet it’s his ability to marry themes such as the whimsy of childhood and its shift into young adulthood, traditional sensibilities clashing against the modern, and nature’s reliance on humanity as well as its indifference toward it in a way that is represented visually as well as narratively that makes him such a master of the craft. It’s the fine details, not just sheer spectacle, that make a Miyazaki film feel like event cinema.

Lady Eboshi is an example of a character meant for a Studio Ghibli world, someone both hardened by circumstances and her perceived place in society, while also someone capable of both hcompassion and cruelty in the same stroke. She wants to kill the Great Forest Spirit, yet houses a community of lepers otherwise ostracized in her village. Her comeuppance, in the end, is to lose an arm from the beheaded mouth of a wolf, showcasing the writer’s belief in this character for a change, her driven by a want to protect rather than greed or bloodlust.

Princess Mononoke is a film in perfect sync with itself.

The enchanting nature of the film is found in the dark and light elements, and the realism is tied with the fantastical. There’s such tireless restraint shown in each frame, from the detailed but deliberate infection seen crawling on the skin and shape of the boars, to San’s movements when she first infiltrates Iron Town or the way her face nuzzles into the fur of Moro. This is a story of larger-than-life gods, Kodoma roaming the forests, and a significant infection that can change the landscape into something unrecognizable.

Yet Princess Mononoke retains its humanity by showcasing the small efforts that make a change along with the universe defying moments of divine, cataclysmic catharsis, such as when the Great Forest Spirt’s body crumbles and, instead of laying waste to those who took his life, inspires growth and the promise of prosperous futures with his death. His fallen body quite literally brings new life to the land.

Advertisement

As is the case with most Miyazaki efforts, the whimsy infused into the film comes with a ready dose of melancholy, aided by the haunting and robust score from longtime Miyazaki collaborator, Joe Hisaishi. This is another aspect that allows Studio Ghibli to help redefine what an animated film is to a more mainstream audience.

Many will recognize the animators that have come before and after him, from the works of Hungarian filmmaker Jankovics Marcell to the adult minimalism from Bill Plympton, to other Japanese filmmakers like the disorienting films from Masaaki Yuasa. Broaden your scope and there’s much more beyond Disney and Pixar and yes, even Ghibli, as films like Princess Mononoke work wonders as gateways for people who have sworn off animated films general. What an absolute loss that is.

It’s hard not to believe in the magic of cinema when witnessing the scene where Ashitaka leaves his home village after being infected and passes through the wonders and perilous unknowns of the countryside. The awe-inspiring moments when the Great Forest Spirit transforms into the Night Walker are as spellbinding for the audience as they are for the characters, so mesmerized by this form so greater than our understanding.

With a mix of CG and hand-drawn sequences, there are as many awe-inspiring landscapes that are illuminated with a golden hue and forests bespeckled by Kodoma and submerged in earthy greens as there are images of carnage and disfigurement. Miyazaki crafted a story of giving and taking, of the need to compromise in order to grow. There’s the want for tradition in hand-drawn animation and the eagerness in progress with the transition to utilizing CG.

Advertisement

The bottom line.

What can be said about this film, its director, and the studio it was borne from that hasn’t been already? I’m 1000 words in, so it would be an absolute lie to say I can’t find the words, but a film of this magnitude is hard to surmise. The legacy it created is evident and it’s championed and cherished by an enormous amount of people all over the world, some of whom are still, enviably, getting to experience it for the first time. I know what it means to my loved ones and how it’s only aided in bonding me with some of my closest friends and family.

I know how much it (along with all of Miyazaki’s work) means to me and how it, along with a few other films, made me look at storytelling and what it can accomplish with new eyes. I’m no artist, but films like this make me wish I were, only so I could understand its pieces, frames, and lines, just a little bit more.

Perhaps that’s what the magic of this film ultimately boils down to. It’s entertaining, yes, with action sequences that will leave you breathless, and as mentioned (a lot), it’s simply beautiful to look at. But it’s the empathetic want to learn more and do more that allows it to linger. The suggested prospect that there’s so much more to explore, so much less to easily define, and worlds upon worlds to discover, is an explosively transformative achievement, even in the subdued and patient hands of Miyazaki. Empathy can be revolutionary.

Princess Mononoke is available to stream now on HBO Max.

Advertisement

Advertisement