My late grandmother connected with James Taylor on a very spiritual level. My mom and uncle would always emphasize her appreciation for the allegorical singer/songwriter of six-plus decades, and it’s quite easy to see why. Upon my deep dive of Taylor’s immeasurable output (particularly during the 1970s, when he was seemingly at his peak), I noticed a comforting versatility that very few artists at the time had accomplished.

He was an opportunist; someone who could change the mood in an instant without sacrificing the naturalistic aurora of an acoustic guitar. He’s a lover, a heartbreaker, and a political activist when he needs to be (his entire Walking Man album seemed to carry intermittent political consciousness). Taylor’s 2016 comments about President Trump suggests that he still cares about what’s going on around him; even if some of what he says feels kind of earnest.

The only possible way any of us could stand the test of time is if we show empathy for one another. As the great author (and holocaust survivor) Elie Wiesel once said, “the opposite of love is not hate, but indifference.” This deep-rooted statement effectively described the apathetic nature of our world as millions of minority groups burned to death at the hands of Nazi Germany during the 1940s.

Wiesel’s bluntness continues to endure as we enter a new decade. America, much like it was during World War II, lives on as a problematic entity ruined by bastardized propaganda and upscale egotism. There’s no integrity or compassion: there’s no “American standard.”

Taylor is such an underrated component of modern American music because he embodied the idea of empathy and passion. I personally wouldn’t visit his music solely off of activism because that was only a small part of his brand. But his message didn’t solely rely on gigantic political messages anyway. Taylor instead picked apart human emotion with the delicacy of a warm spring afternoon. And yet, what he was saying had weight to it. His music contained this wide-eyed clarity even in his darkest moments.

His artistry would more often than not be deceptively ironic. On “Something in the Way She Moves,” Taylor finds love to cope with his helpless demeanor, but cynically understands that most things he leans on eventually lose their meaning. He can also translate this sense of convalescence into earthly tonalities involving drab routine.”Long Ago Far Away” is a perfect example of this.

These cognizant recitals are undoubtedly the reason for why my loving grandmother established a metaphysical affiliation with the 71 year-old. His stark liberalism and self-awareness stayed consistent throughout much of his lifetime, as did my grandmother’s benevolence.

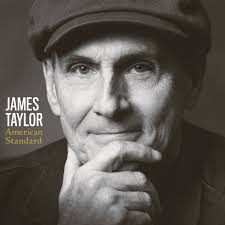

Much like a lot of his contemporaries, Taylor ventures into the occasionally fascinating landscape of performing cover songs. Unlike Sting’s uninspired self-absorption however, JT glances outward into his idea of “American Standards.” He re-establsihes universal classics that have been done countless times before, from Audrey Hepburn’s “Moon River;” to Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child;” to Gene De Paul’s “Teach Me Tonight.”

Advertisement

Taylor not only updates the mixing from obvious technological shortcomings of the past, but he also adds his signature folksy flavor that exudes a classic cozy feeling. Some of the multi-dimensional mystique from some of his best work is oftentimes lost in the easy-listening nature of this album, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t worthwhile tunes.

His rendition of “Moon River” is stripped-back acoustic balladry at its finest, and Alan Jay Ferner’s “Almost Like Being in Love” contains some magical backing vocals and a saxophone lead that calmly touches the record with a fragility of Taylor’s own mind.

In the past, Taylor has shown a great appreciation for country bluesmen such as Howling’ Wolf, and he continues that gratitude on his version of “God Bless the Child,” a monumental message about not taking what you have for granted; which is something a lot of us regularly do (including me).

It should be noted that African American music has always played a heavy role in Taylor’s music, much like every other white soft rocker from the 1950s-1970s. He’s never been the most original guy in the world to be quite frank, but that also doesn’t take away from obvious talent. Walking Man suggests that he was well aware of how much the white man has ripped off black music (“See the white man sailing his ship on the sea/Watch the white man shackle the black man to a tree”). There’s no excuse for this behavior, which is why it’s worth mentioning.

Advertisement

Nothing on American Standard is egregiously bad, but none of it tremendously stands out either. A lot of these songs spin around in my head like one assembly line full of decade-defining parts. Even at its least ambitious, the album still constitutes a wholesome vibe as Taylor ruminates about falling in love as his own mortality starts to hit him (“My Blue Heaven”). “My Heart Stood Still” perfectly encapsulates this reminiscent feeling of picturesque infatuation. It’s one of those few times on American Standard where Taylor finds the perfect “sheet music” to channel his proverbial painting of a peaceful recollection.

My grandmother would’ve enjoyed this album if she were still here. Taylor stills showcases the ability to demonstrate empathy from the simple glow of his amicable voice. He embodies these ideas without explicitly exhibiting them. JT undoubtedly possesses the knowledge of a standup American citizen. One who falls in and out of love as he speaks out against the hellish ales of our spineless world. My grandmother also incorporated these qualities to her own life as a loving daughter, wife and mother. She always looked for the good in people, even at her most doubtful of times. And much like her spiritual leader, she also represented the quiet “American Standard.”

Advertisement