It’s been more than twenty years since the Coens’ last forayed into classic Hollywood cinema with Barton Fink. Unlike Hail, Caesar!, the story in Barton Fink seems to be far less political in their satire and a lot more personally charged (Spoilers to follow!).

At first glance, Barton Fink seems to be a tragicomedy about the worst case of writer’s block in history. However, like all Joel and Ethan Coen films, there is method in their madness. Behind the bizzaro character interactions and the twisty subplots of the titular character, Barton Fink at its core is a work of satire, art imitating life imitating art. Barton Fink is a playwright whose works are deeply rooted in artistic sentiments—so how fitting that he is invited to Hollywood to write a “wrestling picture”, a feature length B movie for $1000 a week (amounting to nearly $14,000 today with inflation.) However, as Barton vociferously announces, he is not about the money or even the critical success. His ambitions are far more idealistic and unattainable.

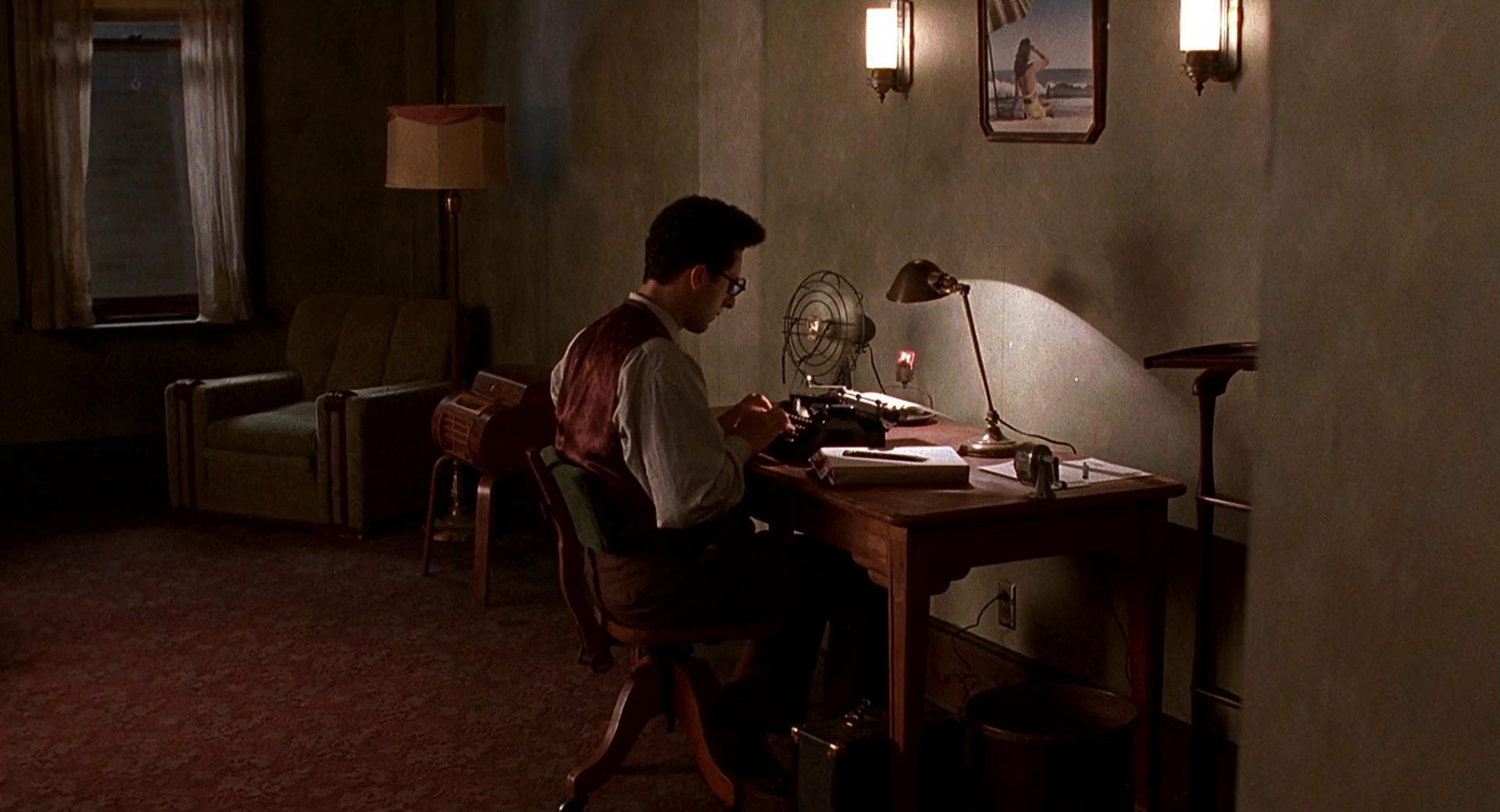

A recurring motif in Barton Fink is the search for the “common man.” First mentioned in the dining room during the film’s opening, he is a hypothetical person whom Barton sees as a kindred spirit; one he searches for on blank pages and a typewriter. He’s not a likable character, Barton Fink. As the film makes abundantly clear, his search for the “common man” is no less phony than the melodramatic wrestling picture that he’s being overpaid to write. So it’s no surprise that the individual he befriends and labels “the common man” turns out to be anything but. He is a murderous psychopath wanted by the police—an ironic twist that ultimately subverts Barton’s supposition on this non-existent, materialized figure. Barton’s journey is both funny and tragic; his many revelations in this film may be harsh but unabashedly honest.

One of the many reasons as to why the Coen Brothers remain two of the industry’s only thriving “mainstream” auteurs is purely due to their films’ nearly mass appeal in even their most ambitious form. The narratives of these films are almost always easy to follow, such as the Odyssey-inspired O Brother, Where Art Thou? When they’re not as easy, like with The Big Lebowski, the two can compensate for its intentionally convoluted, directionless story with relatively simple plotting. The Coens’ chosen style in Barton Fink feels more like a comedy scenario than an art film. Its situational dilemmas, fierce character archetypes and screwball sensibility toward gender roles seem fitting for an early 90s sitcom.

With that said, Barton Fink still remains one of the strongest cinematic statements on “the plight of the artist.” Instead of alienating the viewer with non-linear storytelling and obscure images, the Coens preserve their subtextual nuance, whilst still telling an engaging, comical and endlessly watchable fable on a writer’s artistic and existential neurosis.

Perhaps one of the strongest statements conveyed in Barton Fink can be seen (and heard) plainly at the film’s unofficial climax. John Goodman’s psychotic Charlie, in a strangely poignant soliloquy, reveals to Barton the nature of his mind, how his horrendous crimes against his victims are a way to resolve their personal woes—an act of false patronage, startlingly similar in principle to that of Barton’s attempt to give a voice to the “common man” . . . in a B movie, wrestling picture. The entire scene is a literalized exhortation on crossing the line between artistic integrity and artistic smugness. The latter falling squarely into Barton’s pretentious lap.

To those not interested in the greater ideas presented in the film, Barton Fink—despite its artsy and meaningful storytelling—should really appeal to anyone with a taste for black comedy (a subgenre the Coens rarely blunder.) Its images are still unforgettable with the symmetrical hallways, juxtaposed dim and bright scenery, all of which harken back to the contrastive production design of German Expressionism of the 1920s—a way to emphasize the oddball world the Coens have created. This is definitely not a film that will appeal to all, however, Barton Fink still remains an entertainingly bizarre character piece, equal parts frightening and funny, giving John Tuturro, John Goodman and Michael Lerner perhaps the best performances of the of their respective careers, as well as including yet another magnum opus to both Joel and Ethan Coen’s studded filmography.

Advertisement

Advertisement