Children of the Sea refuses to play by the narrative rules of what audiences have come to expect from this sort of animated film. From the rough lines of the hand drawn animation that contrasts with the smooth digital effects and the glassy, doll-like eyes of its characters to a storyline that pivots messily but effectively halfway through the film into the odyssey of life itself, the film by director Ayumu Watanabe is a lesson in how to impart distinct style into what has come before. There are traces of Princess Monokoes environmentalism and Spirited Away’s heroine in Ruka’s rambunctious stubbornness. There are hints to Masaaki Yuasa’s grounded surrealism and imagery that clearly evokes the haunting visuals of Neon Genesis Evangelion. The stitches from prior works show, but the pattern is entirely Wantanabe’s own.

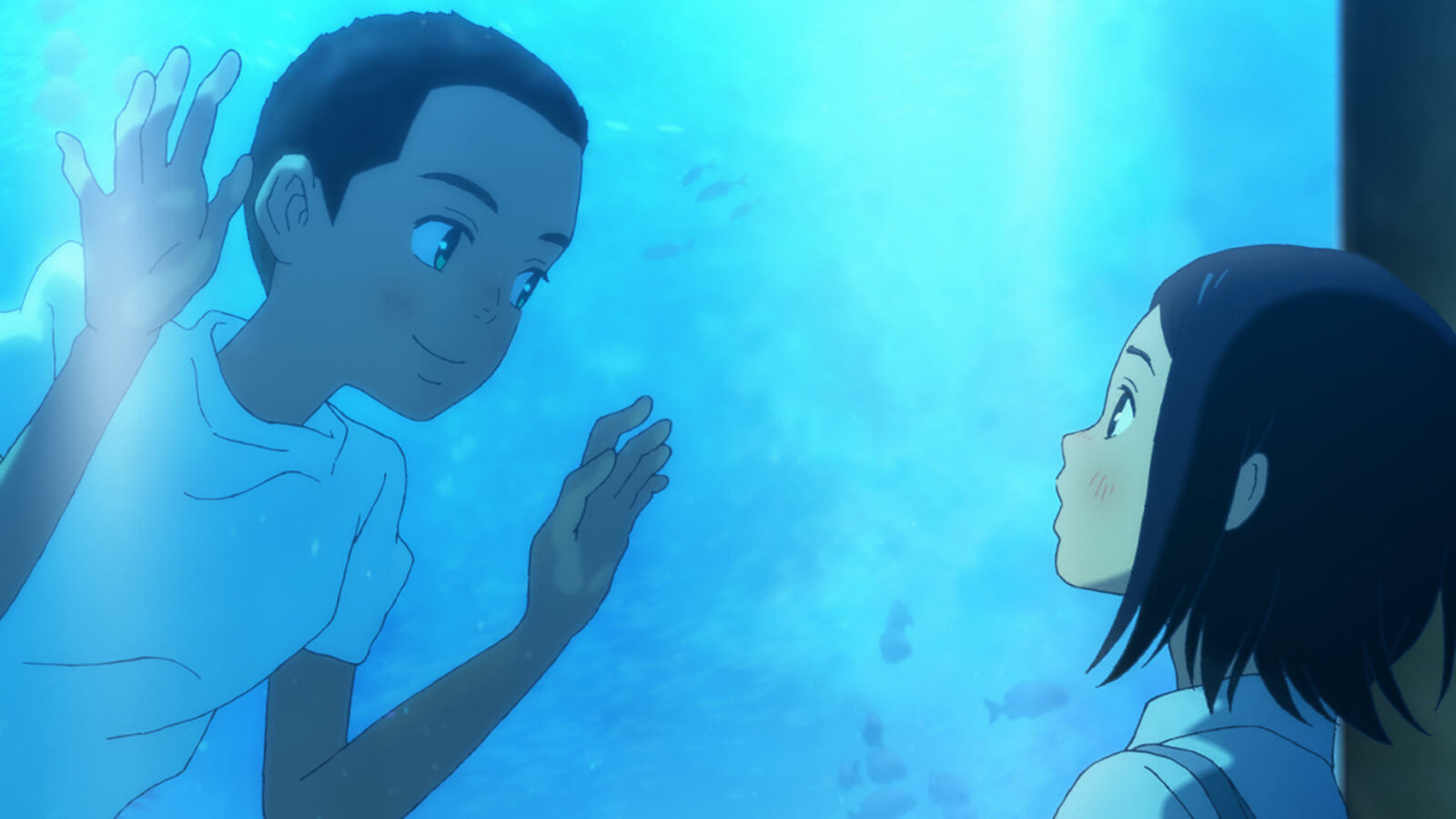

Based on the manga by Daisuke Igarashi (whose work also includes Little Forrest) Children of the Sea follows junior high-schooler Ruka, whose temper has just put her at odds with her summer school club. Our introduction to her is bounding, restless energy, a mindset that plays to the whirling imagery that chases after her as the sky and ocean bleed together, her exuberance and the world’s vastness too large to repress into a single frame. Following her being ousted from the club and rudderless at home, she finds her boredom leading her to the aquarium her father works at, leading her to Umi and Sora, two boys who were reportedly raised by dugong and are being observed by scientists. From Umi’s physical draw to bodies of water to Sora’s striking character design that suggests something not of this world, Ruka is immediately pulled into their orbit and linked to their survival.

While the invisible, immediate bond between the three characters is enough to initially capture our interest, it’s the larger environmental narrative that manages to jettison Wanatabe’s film into its greatest, most dizzying heights. The ocean’s residents have been migrating to Japan, whales are being spotted close to shore and comets are skating across the sky in showers of light, and at the heart of its mystery are two boys who are tethered to the ocean and a girl whose been raised on solid ground. Humanity and nature are so intrinsically tied together in Children of the Sea that the images for both begin to blur.

The animation is superb, at moments as beautiful as it is deeply unsettling. The image of a whale cresting over the ocean is both monstrous and enchanting, and the close up of Ruka’s eyes mesmerizingly haunting as she sees and hears death through a whale’s song. When Sora grows tired from his body’s inability to find home in either sea or on land, his form juts and falters as if being pulled by puppet strings. The climax of the film where the “festival” takes place, the reason for ocean life being so out of sync, is the culmination of these styles as visuals are broken down and composed again – life born anew. So thunderous are these moments, even in their relative, clinical silence, that when the skies clear it feels that we too have been sent tumbling down whirlpools.

Accompanied by the score of frequent Hayao Miyazaki collaborator Joe Hisaishi, the film holds weight through it’s artistry and heart even when narratively, in its biggest moments, it falters, playing with ideas far too big for the box they’ve been given to work in. Hisaishi’s score manages to make one forget that though with its sweeping, fantastical elements and moments of tension that give Children of the Sea it’s more subdued moments.

At the end of the miraculous crescendo when the water stills and what’s left of Umi and Sora is nothing but whispers of wind and stardust big enough to enclose in the palm of Ruka’s hand, Children of the Sea leaves us with a message as equally devastating as it is uplifting for those looking to find meaning in the randomness of life. The movie argues that, in all our imperfections, we are all worthy of containing galaxies; all of existence is composed from the same matter as the stars – lights waiting to be found. We are capable of setting the world ablaze and culpable of those more vulnerable, be they animals or children caught up in our restless greed for knowledge. It’s that worthiness though and the idea that one young girl with all of her initial single minded selfishness could possess heaven and earth and all that lay above and beneath them if she so desired to preserve just one life that allows Children of the Sea to deliver its final impact.

Children of the Sea is now available on Netflix

Advertisement

Advertisement